Farmers still view rice as a symbol of social status. So, the land under Rabi season pulses has transformed into the Boro rice area due to the easy access to irrigation. In addition, the lack of high-yielding seeds, pest and disease pressure, unfavourable weather, etc. made farmers lose interest in growing pulse crops.

As a result, from 2004 to 2012, the area under pulse cultivation decreased to its lowest point. However, by then, Bangladesh Institute of Nuclear Agriculture (BINA) and Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI) had released several improved pulse varieties. But the farmers’ limitations to avail those improved seeds easily at that time might be another reason behind the decrease.

Throughout the year, we require 28 lakh metric tonnes of pulses. The native production is about 9 million metric tonnes. So, 11–13 lakh metric tonnes must be imported annually. Every day, we receive 32–34 games of pulses per person from both import and local sources while 45 games a day are required for a person on an average.

Therefore, we have to produce three times as much as we do now to achieve that goal. Is that even feasible? Only 7 lakh hectares of land are used for the production of pulses at present. Lentils, sometimes called “meat of the poor” are the most widely grown pulse crop. Some 2, 05,668 hectares of land were used for lentil cultivation in 1995–1996; by 2008, it had dropped to 70,850 hectares. It grew to 1, 39, 676 hectares in 2018–19. However, the farmers have discovered a way out of this dire situation after obtaining improved pulse varieties, particularly lentils. It needs to be acknowledged that the entire pulse crop is greatly impacted by this shift in lentils cultivation because the area of land used for the cultivation nearly doubled between 2008 and 2019.

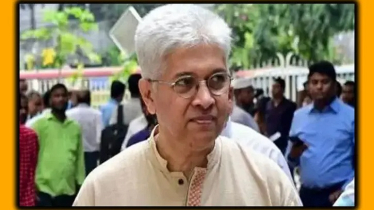

The pioneering role of BARI and BINA in this transition of pulse crops deserves special praise. And we must remember those who worked silently behind them. One such person is Dr. Ashutosh Sarker, a BAU alumnus. He began his career as a pulse breeder. He then joined BARI in the same capacity. He obtained his PhD degree from the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI). As a scientist of BARI, he got an opportunity to work as a Visiting Scientist at the Centre for Legume in Mediterranean Agriculture (CLIMA), Australia. He established the Lentil and Grasspea Breeding Research Programs over there.

In 1996, he joined the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) in Aleppo, Syria, as an International Lentil Breeder. In recognition of his outstanding performance, he was soon promoted to the position of Principal Lentil Breeder and Coordinator of the Food Legume Research Program. In 2008, he was transferred to Delhi and appointed as the Director of ICARDA-related programmes in South Asia and China. He set up ICARDA’s South Asia Food Legume Research Platform in Madhya Pradesh, India, with the overall support of the Government of India. He has more than 300 scientific papers to his credit. Among those articles, the number of articles published in peer-reviewed journals is not less than one hundred and fifty. Several scientists have also done PhDs under his guidance.

Thus, he has ably led global pulse research for 26 years, explored new research areas, supervised pulse research, and played a role in extension. He has developed more than 50 varieties of pulses.

Most of them are lentils. Many of them are tolerant to fragile environments (cold, drought) and the deadly disease Stemphylium blight. Many of them are zinc-enriched too. Under his direct supervision, BARI scientists have been able to develop varieties ranging from BARI masur-1 to BARI masur-9. He also helped in developing BINA masur-7 and Bina masur-10. Out of those varieties, BARI masur-3, BARI masur-6, BARI masur-7 BARI masur-8, and BARI masur-9 are the ruling varieties in Bangladesh. BARI masur-9, a variety of 90 days can be cultivated between the Aman and the Boro, deserved for increasing cropping intensity. Apart from Bangladesh, the farmers of Ethiopia, Morocco, Australia, the United States, Georgia, Uzbekistan, Nepal, India, and Pakistan are cultivating the lentil varieties he developed. In recognition of his work, ICARDA awarded him Scientist of the Year in 2004 and Research Manager in 2009.

There is an approximation of how much Bangladesh has benefited from the breeding lines he developed so far. In the last ten years, the total production from BARI masur-5, BARI masur-4, BARI masur-7, and BINA masur-10 has been 13.5 lakh metric tons. Its international market value is US $1.22 billion, equivalent to Tk 1430 crore in Bangladeshi currency.

From a little-known, quiet scientist who has been researching for 45 years on pulse only, what more could one ask for? For his dedicated research and development efforts in pulse production for our country, he was recently awarded a lifetime achievement award on 10 February 2024 by Dr. Md Abdus Shahid, the honourable Agriculture Minister of the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Aside from that, the governments of Nepal, India, Morocco, Turkey and Australia were pleased with his scientific ingenuity and accorded him the honour he deserved.

Dr. Ashutosh Sarkar retired from his ICARDA assignment some time ago. Now it was time to spend a relaxing day in a Western country. At the same time, he could establish himself as an opportunist social worker by visiting his native land once or twice a year. But that was not what he did. He is still doing something good for Bangladesh. He is now holding the position of ‘Bangabandhu-Chair’ of the Project on Enhancing Science and Capacity Building in Agriculture in Bangladesh, under the care of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University, Bangladesh Council of Agricultural Research, and Global Institute for Food Security, Canada. He still has a chance, in my opinion. Those who are working on pulses in the country can seize this opportunity.

_____________________________________

The writer is a former Director General, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute