Bangladesh’s long-cherished dream of harvesting tuna from its deep sea appears to be sinking. The pilot project launched in 2020 with that ambition has become virtually defunct. Despite plans to purchase two vessels, not a single one has been acquired, and after two extensions of the project’s tenure, progress remains at zero. Millions of taka have been spent without a single day of operation at sea. Mismanagement, corruption, and political interference have left the dream of deep-sea tuna fishing unfulfilled.

The pilot project, titled “Harvesting Tuna and Similar Pelagic Fish in the Deep Sea,” was launched in June 2020 under the Department of Fisheries. It aimed to determine the presence and potential of tuna and similar pelagic species in Bangladesh’s deep and international waters, encouraging private investors to purchase vessels and venture into deep-sea fishing.

Initially, the project was scheduled from July 2020 to December 2023 with an estimated cost of Tk 61 crore. The deadline was later extended to June 2025, and the budget was revised downward to Tk 55 crore, reducing the number of proposed vessels from three to two. However, neither vessel was procured. The term was further extended by two years this year, and the cost reduced again to Tk 41.04 crore. Despite these changes, overall progress has been limited to just 6.85 percent. Although a letter of credit worth Tk 21 crore was opened for the vessels, no marine surveys have been conducted, no data has been collected, and no database has been established. Ironically, before purchasing any vessels, the project spent Tk 11 lakh to buy three digital cameras intended for the ships.

The first tender for the vessels was floated in March 2021, but none of the three bids were accepted. A second tender in August that year awarded the contract to Singapore-based Uni Marine Private Limited, represented in Bangladesh by Computer World BD, owned by former Bangladesh Chhatra League president Liaquat Sikder. However, government restrictions on vessel imports caused long delays. In May 2024, a seven-member delegation from the Fisheries Department and Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock visited China to inspect the ships. The contractor presented low-quality vessels fitted with decade-old engines.

Project Director Dr. Zubaidul Alam stated that the contractor attempted to supply old ships despite the tender’s requirement for new ones. “When we refused, Liaquat Sikder threatened us with weapons,” he said. “If we had accepted those ships, the state would have suffered huge losses, and the Anti-Corruption Commission would have later filed cases against us. We have decided not to purchase any vessels. Instead, we will lease ships from a foreign company to conduct research and formulate a master plan.”

Several officials of the Fisheries Department, requesting anonymity, said former Fisheries and Livestock Minister Abdur Rahman had pressured project officials to accept the old ships. When they refused, the project’s progress came to a halt.

Director General of the Department of Fisheries, Dr. Abdur Rouf, admitted the project has failed to achieve its objectives. “The tuna project’s tenure has been extended, and we are trying to expand its activities through the ministry,” he said.

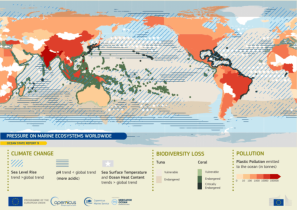

Despite no fishing activity, Bangladesh continues to pay fees to international organizations. The country’s maritime territory spans about 218,000 square kilometers, comprising 20 percent coastal waters, 35 percent shallow sea, and 45 percent deep sea. Bangladesh also holds the right to operate in international waters. However, modern longliner and purse seiner vessels—essential for deep-sea tuna and pelagic fishing—are not available in the country.

A review meeting held at the Fisheries and Livestock Ministry in September 2023 revealed that although permission was granted to purchase 19 such vessels, not one has been bought. Neither the Department of Fisheries, the Fisheries Research Institute, nor any local university possesses reliable data on the population, biology, breeding, or migratory patterns of tuna and other pelagic species. Experts argue that approving vessel purchases without such foundational research was irrational.

In 2018, Bangladesh gained full membership in the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), giving it the right to fish in the international waters of the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. However, since obtaining membership, Bangladesh has yet to fish in international waters, even though it pays an annual membership fee of about Tk 7.7 million.

As an IOTC member, Bangladesh receives data on fishing activities, technologies used, and catch statistics from other nations. Yet experts question whether full membership was necessary, since similar data could have been accessed as an observer country with much lower expenses.

A Fisheries Department official, requesting anonymity, said, “We joined the IOTC without any preparation. Bangladesh has no capability to fish in international waters. Now we are paying money every year without catching a single fish. This was done mainly to facilitate foreign trips and gain publicity for certain officials.”

Professor Kazi Ahsan Habib, Dean of the Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science at Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, said that scientific data must come first before deep-sea fishing begins. “We must know where tuna are found, their breeding cycles, and migration routes. Countries like Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and India have advanced in tuna harvesting and exports, but Bangladesh remains stuck in its initial phase,” he said.